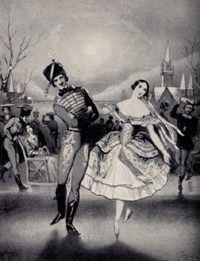

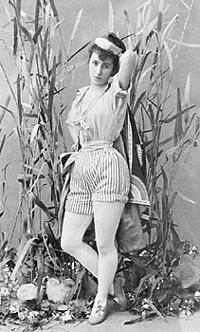

Mathilde Kschessinskaya as Ondine

in the Pas des Travestie from the Pugni/Petipa/Perrot

"

Ondine", St. Petersburg, 1899

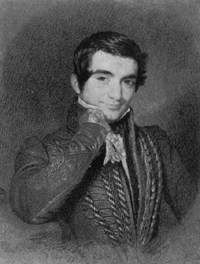

Césare Pugni (1802-1870)

Cesare Pugni was an Italian composer of ballet music, while in his early career he scored Bel canto Opera , symphonies, and various other forms of orchestral music quite successfully. He is most noted for the ballets he scored while serving as Ballet Composer to Her Majesty's Theatre in London , and First Imperial Ballet Composer to the Romanov's Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg , collaborating with such distinguished choreographers as Jules Perrot , Arthur Saint-Léon , Paul Taglioni , and Marius Petipa . Pugni is the most prolific composer of the genre of ballet music that has ever lived - by the end of his life he had scored 312 original ballets, and a gargantuan amount of various Pas and incidental dances, such as divertessments, variations, and additional music for interpolation into already exsisting works, as well as adapting and revising scores for ballets by other composers. Of the original ballets for which Pugni wrote music, he is most noted for Ondine (1843); La Esmeralda (1844); The Pharaoh's Daughter (1862); and The Little Humpbacked Horse (1864). Of the various Pas and incidental dances, etc. for which he scored music, he is most noted for the Pas de Six from La Vivandière (1844); the Pas de Quatre (1845); the Venetian Carnival Grand Pas de Deux (AKA The Fascination Pas de Deux from Satanella ) (1859); and his additional music for the ballet Le Corsaire (1856, 1863).

There will likely never again be a greater contributor of music for the art of ballet than Cesare Pugni, who is without question the most prolific composer of the genre that has ever lived. The poet and historian Donald Sidney-Fryer 's A Checklist of Ballet Scores by Cesare Pugni puts the number at 312 complete ballets, the majority of which were written for the most influential choreographers of the 19th century from Milan , to Paris , Berlin , London , and finally St. Petersburg , among them - Jules Perrot , Arthur Saint-Léon , Paul Taglioni , and Marius Petipa . Nearly every great Ballerina of the Romantic epoch, from Marie Taglioni to Fanny Cerrito, Lucile Grahn , Fanny Elssler , Carlotta Grisi , and Carolina Rosati , all danced the majority of their legendary triumphs in ballets set to his music. In Pugni's early career, mostly while in Milan, he also scored five well-received Bel canto operas , over forty masses , 4 (known) symphonies , and many other orchestral pieces, the majority of which were written for small ensembles such as string quartets .

Historians are not certain of the exact year of his birth, as it has been given as both 1802, and 1805. Likewise the place of his birth is not know for certain either, as both Milan and Genoa have been given. The most authoritative facts concerning the composer's birth appear to be Genoa, Italy on May 31 , 1802 . His father, Carlo Pugni, was a well-known clockmaker with a successful shop in the Pallazzo del Duomo , near Milan 's cathedral . It is interesting to note that the word Pugni means fists in Italian.

It was certainly in Milan that the young Pugni received his musical education, though he was not instructed at the Milan Conservatory as has been stated by many historians. He began his musical studies at a very young age, likely by way of private lessons, under Bonifazio Asioli , who taught him composition and counterpoint , and from Alessandro Rolla , who for many years was lead violinist in the orchestra at La Scala and a prominent composer, who taught Pugni the violin (Rolla is also noted as the teacher of the young Niccolò Paganini ). Other names associated with Pugni's musical training are Peter Von Winter and Carlo Soliva , both of whom scored operas for La Scala between 1816 and 1818. At the age of seven Pugni scored his first composition, probably for the violin , an instrument he excelled in. In time Pugni, began to show a great facility for composition, with an extraordinary talent for creating melody and for orchestration.

It appears that the first ballet to have been associated with the composer was the Balletmaster Gaetano Gioja 's (teacher of Fanny Elssler ) Il castello di Kenilworth ( The Castle of Kenilworth - based on Walter Scott 's novel Kenilworth ), produced at La Scala in 1823 ( Gaetano Donizetti would later write his opera Il castello di Kenilworth based on the same theme). The printed libretti for this work credits the music as being a pastiche of themes derived from "various well-known composers", for which Pugni himself adapted the music. In 1826 Pugni received his first commission for the ballet Elerz e Zulmida , to be mounted by the Balletmaster Louis Henry . The success of that work brought about three more commissions from Henry, and soon Pugni was sought out by some of the most distinguished choreographers then working in Italy, among them Salvatore Taglioni (uncle of the legendary Marie Taglioni ), and Giovanni Galzerani . Pugni's growing popularity as a capable composer of light, melodious music for dancing was attested by the publication of a number of piano reductions of excerpts from his works, among them, the popular Scottish Dance from his 1837 ballet L'Assedio di Calais ( The Siege of Calais ), which like every one of his works which was published throughout his life and career sold very well.

Though he demonstrated considerable talent for composing ballet music, Pugni's real ambition was to become a celebrated composer of opera. There had been occasions where he had been commissioned to compose an aria "to order" for various performances at La Scala, and such assignments encouraged him to pursue his ambition further. In 1831 his opera Il Disertore Svizzero ( The Swiss Deserter ) premiered at the Teatro Canobbiana in Milan, with his teacher Alessandro Rolla as conductor. The work was praised for its variety and originality, and was revered by the composer's fellow musicians. Pugni's next opera was La Vendetta , produced at La Scala in 1832, premiering with great success.

It was during this time that Pugni began to compose a substantial number of masses , symphonies , and various other orchestral pieces. One Sinfonia in particular was scored for two orchestras, both playing the same piece with one orchestra a few bars behind the other. This piece so impressed Giacomo Meyerbeer that he was known to hold up a manuscript of the work in order to show his friends a supreme example of virtuosity in composition. Such success as a musician appropriately coincided with his appointment as Maestro al Cembalo (or Director of Music ) at La Scala. Next to this appointment Pugni also taught the violin and counterpoint when time allowed. He even instructed the visiting Mikhail Glinka , who revered Pugni as a composer and teacher of music.

Pugni scored two more operas for the Teatro Canobbiana in 1833 and 1834, both of which were listened to with considerable respect (many historians have claimed that Pugni's last three operas were utter failures, which is wholly inaccurate). Pugni also continued composing various orchestral pieces, all of which were earning him great prestige and notoriety.

It would seem that all of the composer's ambitions were about to be fulfilled, especially that of becoming celebrated composer of opera, for which he had put forth much effort in laying the groundwork. But only two years after his appointment as Maestro al Cembalo , all of his prospects collapsed, and he was dismissed from La Scala for what appears to have been the misappropriation of funds, a likely by-product instigated by his notorious passion for gambling and liquor. The post of Maestro al Cembalo was taken over by Pugni's two assistants, Giacomo Panizza and Giovanni Bajetti . In 1834 the composer left La Scala in utter disgrace, and did not return to Milan for many years.

ParísLondon

In 1843 Pugni accepted a position as Ballet Composer at Her Majesty's Theatre in London from its director Benjamin Lumly . These were very successful and productive years for the composer, where between the theatre's 1843 and 1850 seasons Pugni produced an impressive series of scores for three of the greatest choreographers at that time: Jules Perrot , Arthur Saint-Léon , and Paul Taglioni . Working under pressure and having to meet deadlines drove Pugni to produce, as he had no problem meeting the heavy demand for ballet music. Next to the complete ballets he composed during his time in London, he also scored a substantial number of supplemental Pas , variations, divertessments, and incidental dances. In 1845 alone he produced six new scores, including the celebrated divertessment Pas de Quatre . His music was always highly praised by the public and critics alike - his almost super-human capacity for creating a nearly endless variety of lively, infectious, and danceable melodies was all the more accented by his clever and colorful orchestrations.

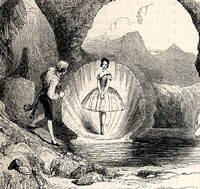

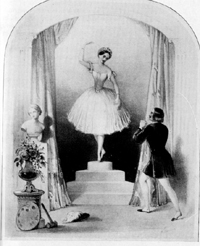

Jules Perrot always made certain that Pugni was involved in composing the music for his work, as from 1843 on-wards few ballets were produced by him that did not have Pugni as composer. Nearly everyone of these works were great successes, and the public and critics marveled at how fresh and new both choreographically and musically each spectacle was. In 1843 Perrot produced Ondine , a tale of a jealous Naiad inlove with an Italian fisherman, for the great Ballerina Fanny Cerrito , for which Pugni wrote one of his greatest scores. In 1844 Perrot produced his most celebrated and enduring work, the spectacular La Esmeralda for the great Ballerina Carlotta Grisi , set to Pugni's joyous music. In 1846 Perrot produced the oriental extravaganza Lalla Rookh for which Pugni composed a score full of Arabian influence, and that same year Perrot and Puigni also mounted the celebrated Catarina , which was one of Lucile Grahn 's greatest triumphs.

It was throughout the late 1840s that Pugni began to collaborate with Paul Taglioni and Arthur Saint-Léon on a regular basis, who were both occasionally engaged in London as guest choreographer. During this period Pugni was composing four to five full-length works every year between these choreographers and Perrot, and showed no signs of it weighing down on his fantasy. Pugni left a profound impression on Saint-Léon, who was just as skilled a musician as he was a dancer and choreographer. During the 1840s Saint-Léon was engaged as Balletmaster at the Paris Opera, and Pugni traveled there often to score music for the choreographer's works. Pugni and Saint-Léon created many successful works while in Paris, among them, La Vivandière in 1844, La Violon du Diable in 1849, and Stella in 1850, for which Pugni wrote a score filled with a great variety of sparkling Neopolitan melodies.

In the short span of their collboration Pugni wrote many wondrous scores for Paul Taglioni, who would later site Pugni as the greatest composer of ballet music he had ever worked with. In 1847 Pugni wrote no less than four short ballets for Taglioni, among them - the lavish Coralia where a woman falls inlove with an English Knight, and the magical Thea where the Flower Fairy brings together a harem maiden and an Arabian Prince. Taglioni's 1849 The Winter Pastimes was set to Pugni's scintillating music suggesting an enchanted wood in winter, and in 1850 Taglioni produced Les Métamorphoses , where a distracted student is taught a life lesson by a sprite.

During the 1840s Pugni accompanied Perrot on many occasions to stage a substantial number of their ballets in various theatres throughout Europe. In 1845 they staged La Esmeralda for La Scala in Milan, and later that year for the Court Opera Ballet in Berlin, where the title role was danced by the great Fanny Elssler . In 1847 Pugni and Perrot mounted Catarina for La Scala, where they returned later that same year to stage Lalla Rookh . In 1848 Perrot was invited at the behest of Fanny Elssler to stage La Esmeralda for the great Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg, Russia. While in the Imperial capital Perrot was offered the position of Maître de Ballet (First Balletmaster/Chief Choreographer) to begin in the 1850-1851 season, which he accepted.

Postcript

It is significant to note that three of Cesare Pugni and Daria Petrovna's descendants danced with the Imperial Ballet - his son Nicolai Cesarevich Pugni, who danced in the Corps de Ballet from 1882 until a few months before his death in 1896. Another was his granddaughter Léontina Konstantsiia Tsezarevna Pugni, daughter of Pugni's son Cesare Cesarevich, who danced as a soloist from 1903 to 1913 as well as touring Scandinavia and Germany with Anna Pavlova 's company from 1908-1909.

Pugni's grandson Alexander Shiryaev , son of Pugni's daughter Ekaterina Cesarevna, was a much celebrated soloist and character dancer in St. Petersburg. He served as the Imperial Ballet's second Balletmaster, succeeding Lev Ivanov upon his death in 1901. Shiryaev later served as Balletmaster to the post-revolution Imperial/Petrograd Ballet. Shiryaev revived many ballets, among them Petipa's staging of Pugni's Ondine with Anna Pavlova in the title role, as well as the first post-revolution Nutcracker staged in Russia, with Fedor Lopukhov , along with many other works. Another of Pugni's grandsons is the celebrated artist Ivan Puni (or Jean Pougny) (1894-1956), son of Pugni's son Albert Linton-Pougny (1848-1925), who was born of his second wife, Marion Linton.

After Saint-Léon's death in 1870, Petipa was named Maître de Ballet , selecting Léon Minkus (1826-1917) as Pugni's successor as First Imperial Ballet Composer to the Imperial Theatres. Minkus held the post from 1871 until 1886, when it was abolished by the director of the Imperial Theatres Ivan Vsevolozhsky . Minkus would score the music for such ballets as Petipa's Don Quixote (1869), and La Bayadère (1877), among others

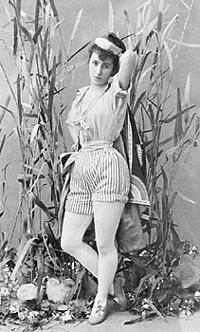

Mathilde Kschessinskaya as Ondine

in the Pas des Travestie from the Pugni/Petipa/Perrot

"

Ondine", St. Petersburg, 1899